Popular cults and their relationship with organised religion has been studied for several decades, not only by curious social scientists, clinical anthropologists, sympathetic folklorists, scholars of language and literature, religious or ritual practitioners as well as several other categories of observers. The two way transactions are the main elements but in this short report, we will focus on one specific aspect in one site over a long period to understand the inexorable process of appropriation of the mainstream religion. The chief focus of this article is on the ancient folk deity of Bengal, Dharma Thakur, and its worship in Jamalpur village of Purbasthali thana in the district of Barddhaman, West Bengal. Here, the deity is known by the name, Buroraj, that is supposed to combine two deities, Buro for Buro-Shiva which is a common name for the mighty god of organised Hinduism and the other half standing for Dharma-raj, the popular folk god 1 of the western Rarh tract of Bengal or West Bengal. With every progressing year, however, the association of this autochthonous deity with Shiva is getting more and more pronounced and now most people seem to have forgotten the popular origin of the name. In fact, this is the journey that I have observed from the mid-1970s, over a period of 25 years that I shall narrate in this article to indicate the dynamics of the process of religion.

I have personally visited the site in 1976, 1981, 1986 and 1998 during the main festival of the deity which coincides with Buddha Purnima or the full moon 'day' of the second month of the Bengali calendar known as Baishakh . The Buddha is believed to have been born on this date and it usually falls some time in the middle of the month though wide variations are also common. I visited the village on three other occasions in the 1990s during other months of the year, when it had resumed its normal life as different from the days full of action and excitement at the time of the festival when large crowds of worshippers 2 and other fun seekers descend upon the innocuous village in the heart of Bengal. I must mention at this point that I was not a researcher or academic, but that I had a full time transferrable government job, which restricted my flexibility to be present in the field all the time. But I had a great advantage as Gopikanta Konar, professional field researcher, sociologist and Barddhaman expert became my collaborator from an early stage. He stayed at Barddhaman town and taught at Memari College in the same district, not too far away from Purbasthali thana. Konar and was continuously covering fairs, festivals, rituals, customs and worships all over the district.

Though we started as independent researches, our work converged as we both realised that we were actually witnessing the step by step process of 'appropriation' of an autochthonous worship by the mainstream religion. Konar ensured a regular stream of data on the deity, its worship rituals, the annual festival and the village in general. Our study, therefore, covers a longer period if one intersperses data from Konar's notes but that is really not required for this article as the trends that I shall mention are fairly well evident in their own right from my notes and observations. I started photographing in the 1980s and moved to colour photos in 1997, but some of the better quality photos that I have appended were taken by Amol Ghosh, who made a professional documentary film on the festival in 1997. Some are from Konar's collection and in Arup Sengupta provided photographs of the festival on Buddha Purnima day in 2014. The work thus spans over a period of almost 40 years and observes how the religious processes actually function and to what end. Though we have materials from 78 sites of Dharma worship in the districts of western Bengal, I have concentrated on Jamalpur because it helps to identify specific traits in a single site that exemplify the two tendencies mentioned, ie, 'appropriation' and 'accommodation'.

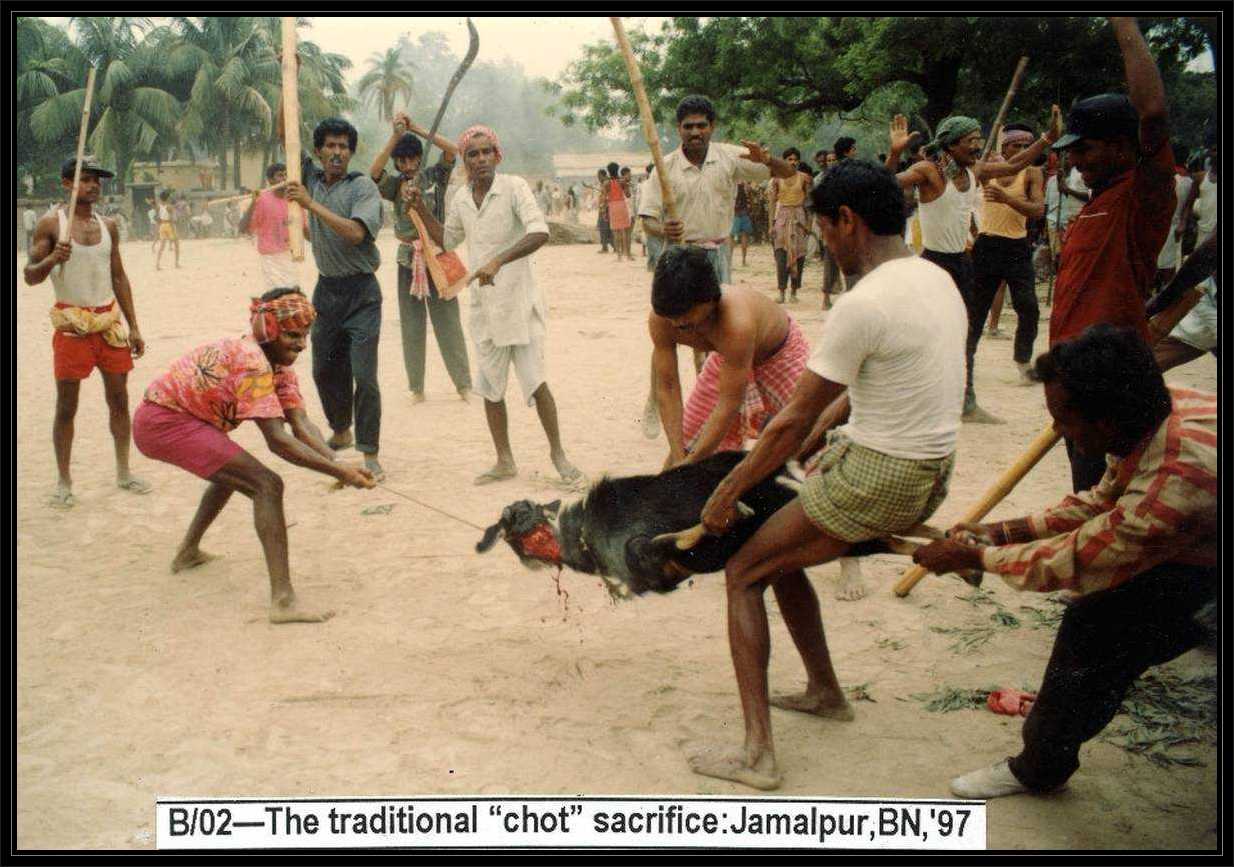

In 1976, I first stumbled upon Jamalpur village on the basis of a narrative written in the late 1950s by the travel writer and social commentator, Benoy Kumar Ghose. His Paschimbanger Sanskriti 3 had earned considerable repute since its publication in 1959 as it introduced readers to various interesting aspects of lesser known festivals, historical places, religious sites. He spoke of large crowds of pilgrims who landed in this village a day or two before the full moon of Baishakh each year and how hundreds of animals were slaughtered on Purnima day in the open field. Unlike standard sacrifices that were done with prescribed religious rituals on sanctified wooden altars, haarikaath , in front of temples and deities, in this village goat and sheep were killed at some distance away from the temple. He mentioned that animals were killed in a manner that was popularly known as the chot or kop method, where one person folded its four feet backwards under his arm, or held the creature tightly on to the ground. The other person tugged at the rope that went around its neck as a noose and the head was then chopped off in mid air without any support or ritual chopping block. I have placed two photos as pics 1 and pic2 to explain this, as little had changed when I visited the site in 1976, 1981, 1986 or 1988. This old system of sacrificing that arose spontaneously from the local population continues till date, not only in Jamalpur but in a few other sites as well, even though it is not according to Hindu ritual procedures.

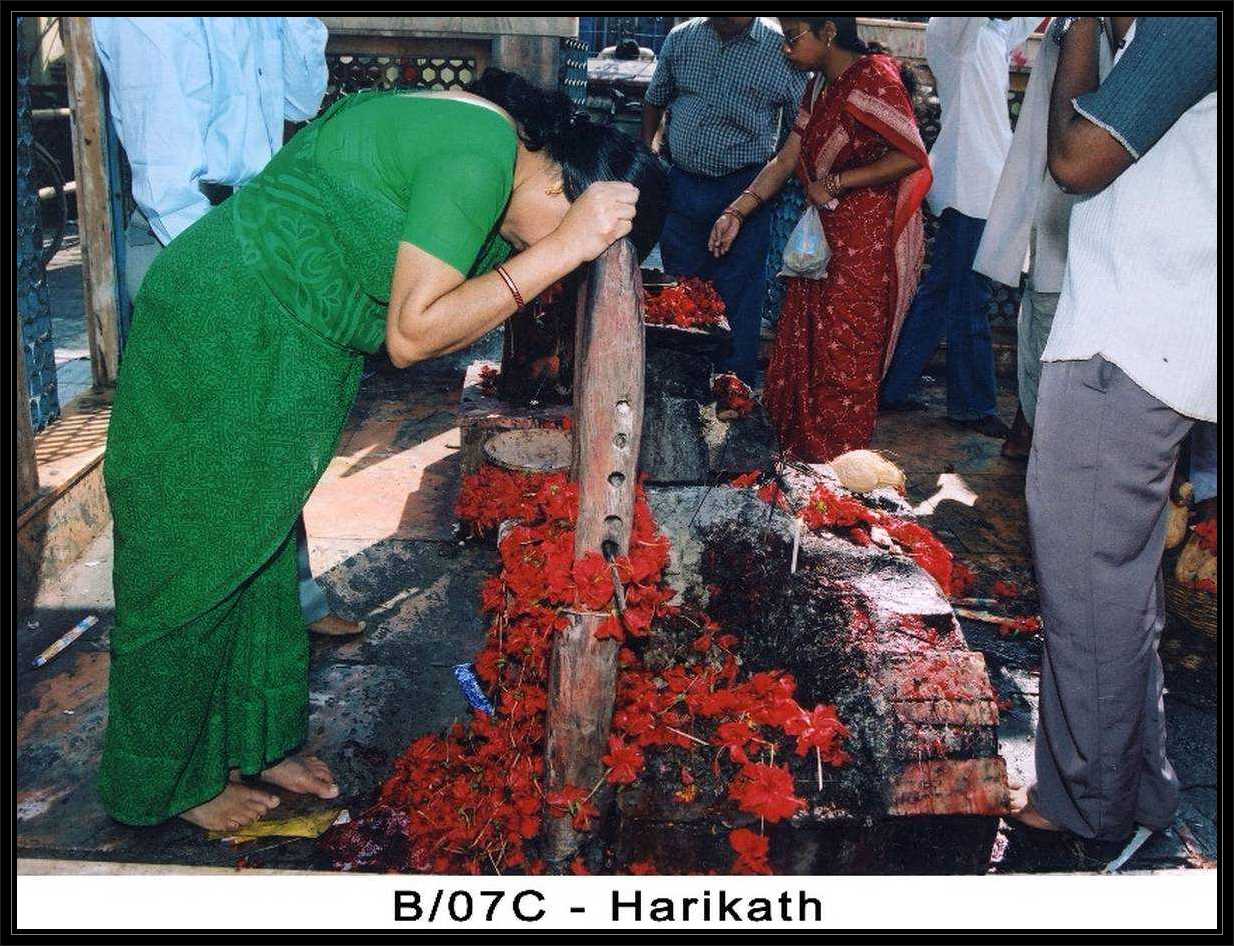

But what I observed over the years was that increasing numbers of animals are brought before the temple and 'blessed' by the priests before they are taken to the open fields for slaughtering. The priests say a few mantras; place garlands of blood red hibiscus on their necks and smear vermillion on their heads, as a ritual that hovers half way between the original indigenous practice and the later 'official' Tantrik method of sacrifice. The gradual adoption of the practices of the mainstream religion was increasing each year and by now, almost all the animals are brought before the temple first for blessing, which was not considered a necessity at all in the late 1950s when Ghose reported or even in the 1970s or 1980s, when I visited in the village. Besides this token act of consecration, a certain number of animals are also slaughtered in true or full Hindu style, at the haarikaath ( an indicative photo is placed as pic 3 ) in front of the temple, which indicates an increasing adoption of the 'great tradition'.

This is part of the appropriative process where not only the priests but those who have "more religiously knowledge" or are inclined towards "proper religious observances" carry on a continuous advice that real merit can only take place only when this proper process, ie, the haarikaath method is adopted. This 'formalisation' then includes other costs and partners, and other than fees or dakshina, parts of the animal have often to be given to the officially appointed group. It is clear that this group monopolise the business of slaughtering animals with the blessings of the priesthood. In Jamalpur, it is the subaltern Bagdi caste that enjoys this share, but we will mention the reasons later.

In most other places of this cultic worship all over Bengal, this part of the process of Sanskritisation is complete as all the sacrifices are held before the temple or in the precincts, observing all prescribed rituals. In fact, oddities are noticed in the ritual of slaughter even now, like in the village of Ray Ramchandrapur, where the prosperous agricultural community of Aguris have taken over the worship9 of Dharma Thakur from the leather workers' caste. A tall altar provides for multiple sacrifices, that starts with one single animal after which 3 are placed on top of each other and killed in one stroke. This is followed by 5 and then 7 in one single stroke, with the finale at an incredible 9 creatures being beheaded with one sharp and powerful blade ( pic 4 ).

One can imagine the frenzy as the numbers of goats for slaughter go on increasing and it is clear that while ritual sacrifices per se have been "reined in", their autonomous character finds non-prescribed expression. Besides, religious celebrations also provide occasions for competition in the village or within the larger community, as the better off display their wealth by increasing their contribution, directly or indirectly. The worship of this humble cultic deity had no such pretensions as it was organised by the poorest groups in true community spirit, but the later formalisation of religion by the priestly class ensured that individual religious merit, through such contributions, mattered more. Lastly, we must remember that the sacrificial altar is useful throughout the year, as it has a religious consequence even when not in use and many worshippers actually pray to it, seeking strength and blessings ( pic 5 ).

However innocuous they may appear, each ritual and each small "instrument" has its utility in the business of religion and this applies, more or less, to all though degrees may differ.

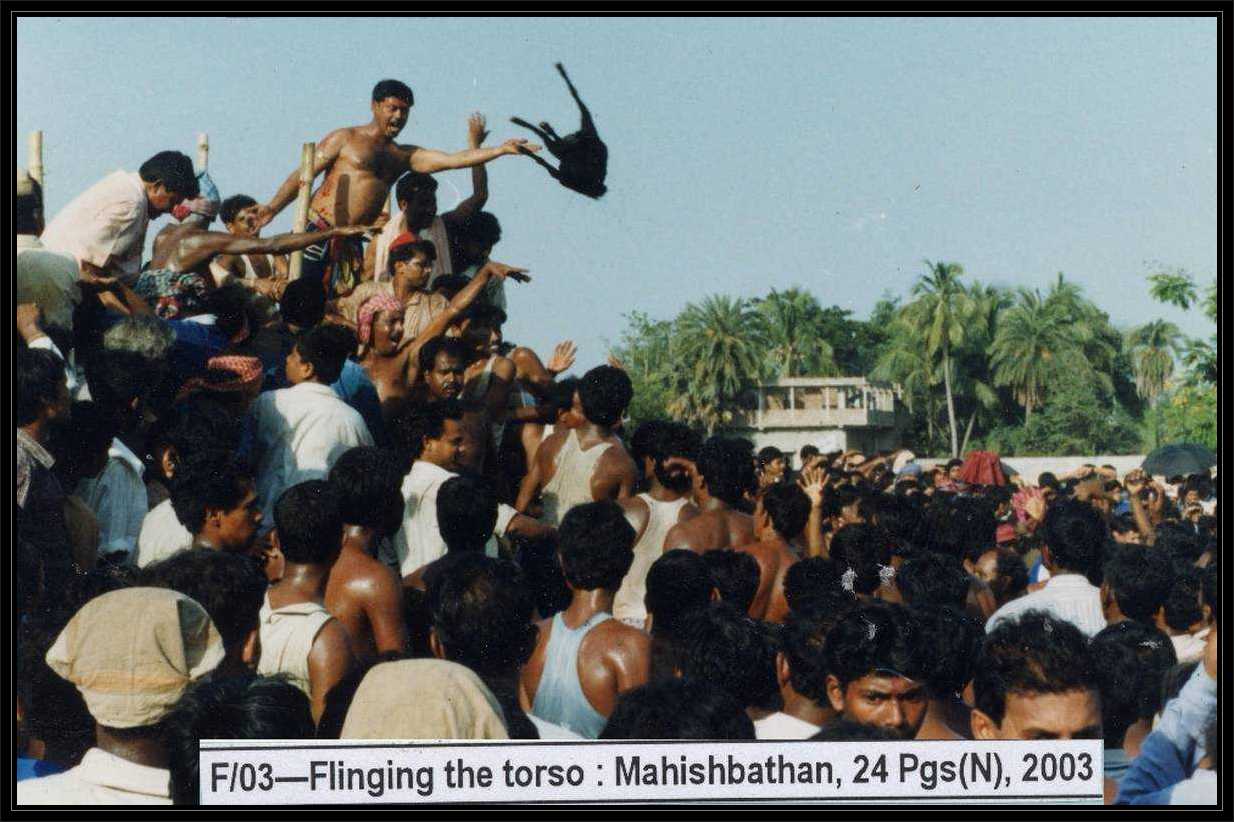

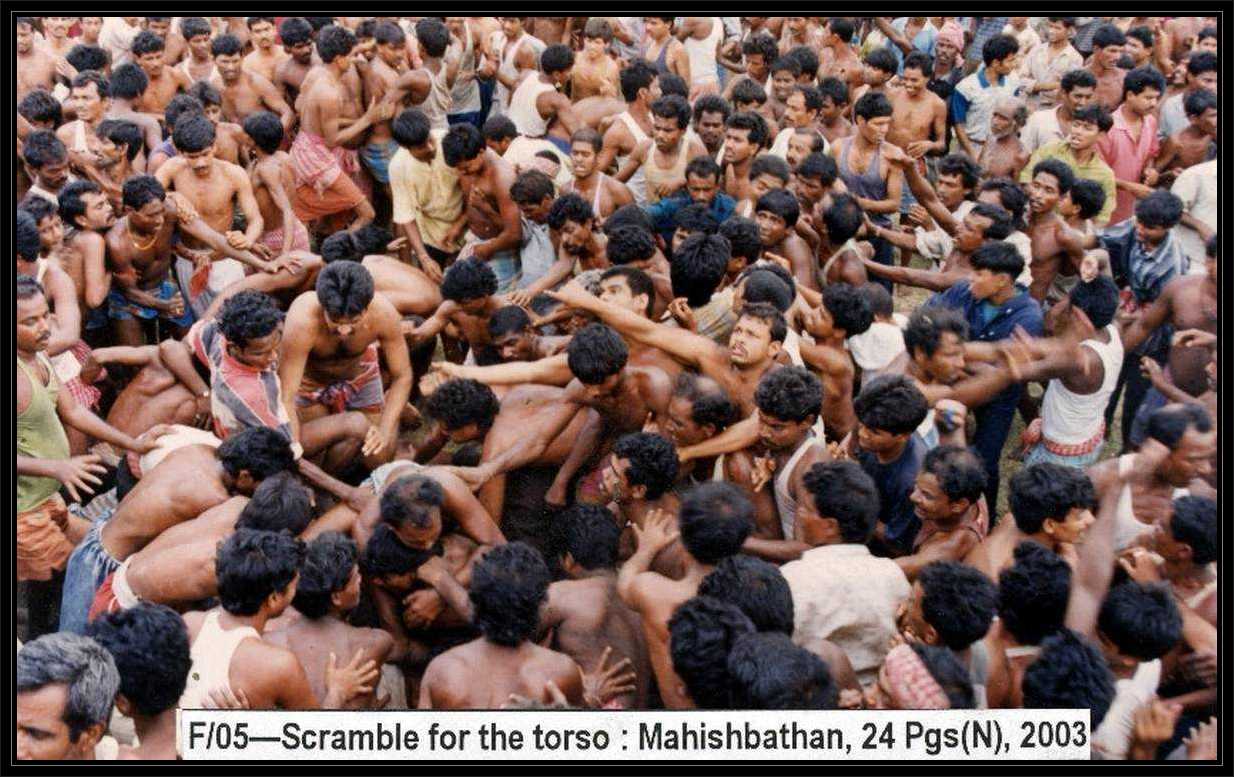

Benoy Kumar Ghose mentioned how excited crowds in Jamalpur had scrambled for the heads of the animals as they rolled off on the ground. It was a free for all ritual called muro kara, that was like the game of rugby where the player who grabs the ball is pounced upon by others in a rather rough, martial sporting event. By the time I went there almost 18 years later, these games had almost disappeared but I could still see an occasional scramble for the heads of the animals. It was a bloody sport as it was no holds barred. There were reports of how after the animal was slaughtered, the whole torso of the decapitated animal was flung up into the air and how crowds engaged in a fierce competition to grab the body, more as a rough sport than as an act of piety. Though I saw none of this in Jamalpur, I came across this very practice that was continuing in Mahishbathan in the middle of the first decade of the 21st century, as untamed and unshackled as before. The mad fight for the body of the sacrificed animal has to be seen to be believed. have placed two photos as pics 6 and 7 that give a rough idea but can hardly do justice.

This is rather strange as this 'village' is on the northeastern outskirts of Kolkata, but is now part of the Rajarhat New Town area and an integral part of the modern Kolkata metropolis, where Sanskritisation and the overriding of non-Hindu (or even pre Hindu) cultic practices is assumed to be complete. There are two issues here, one that rituals like this worship that were performed by more "martial" or "muscular" social groups provided a forum to them for annual competitions of bodily prowess and negotiating skills that earned the victors community respect and recognition, that formal Hinduism in Bengal hardly accorded them. Second, such fierce competitions must have been sustained over centuries by other forces, and it is my submission that these annual competitions must have also acted as "recruiting centres" for zemindars and others who retained retinues of strongmen to ensure that their writ ran, with the use of muscle power.

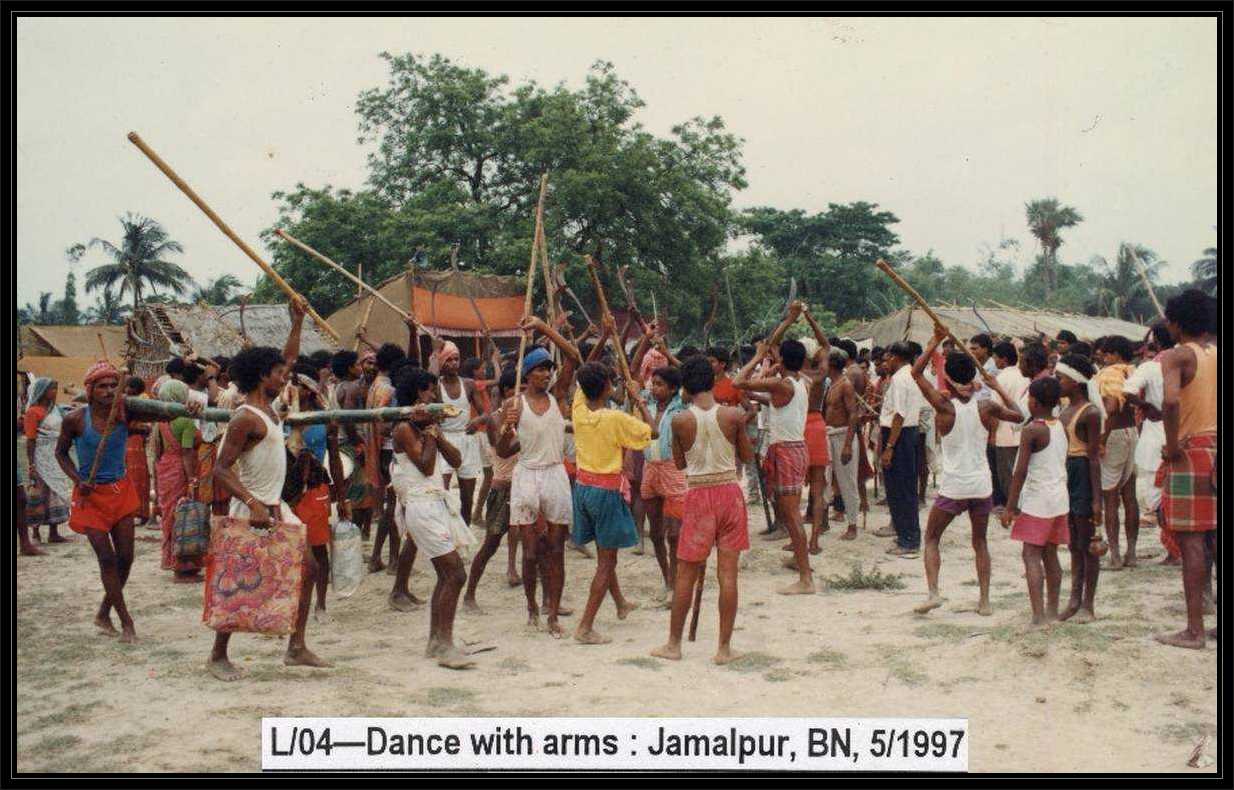

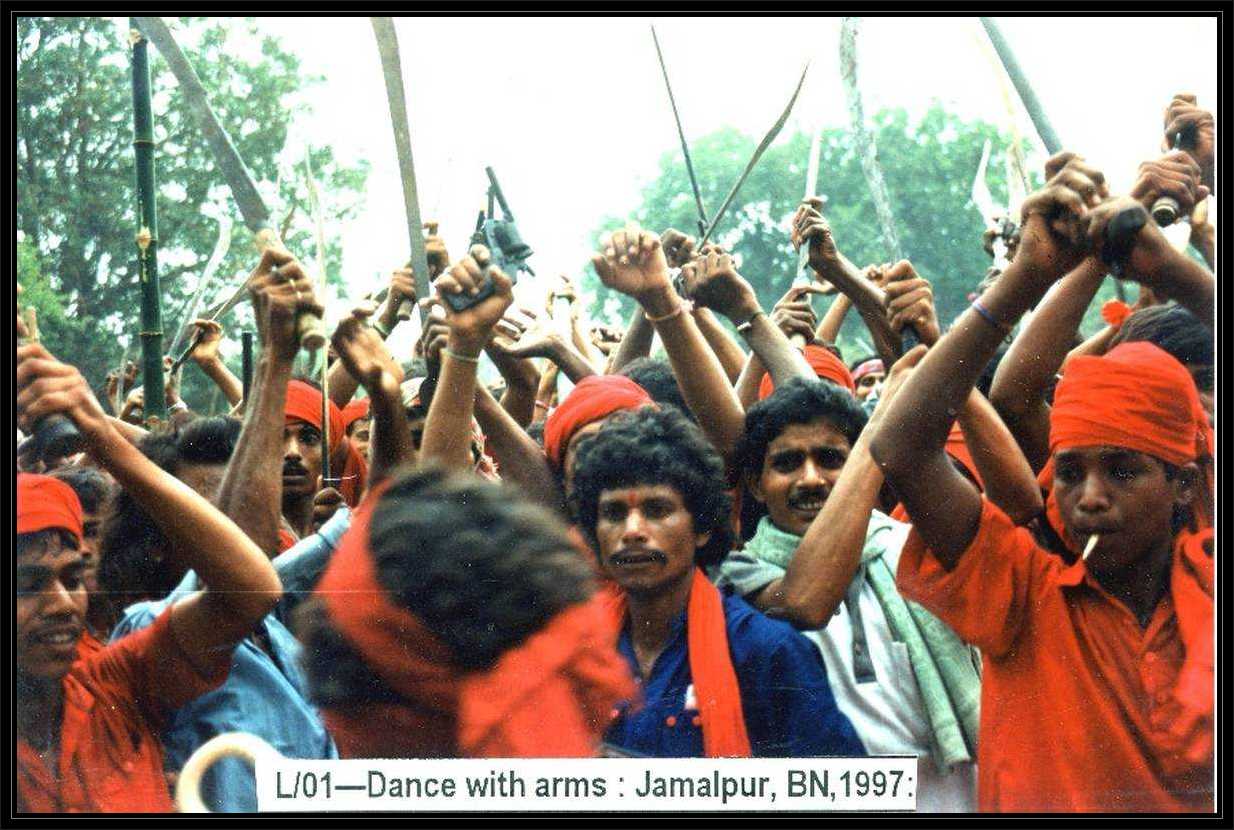

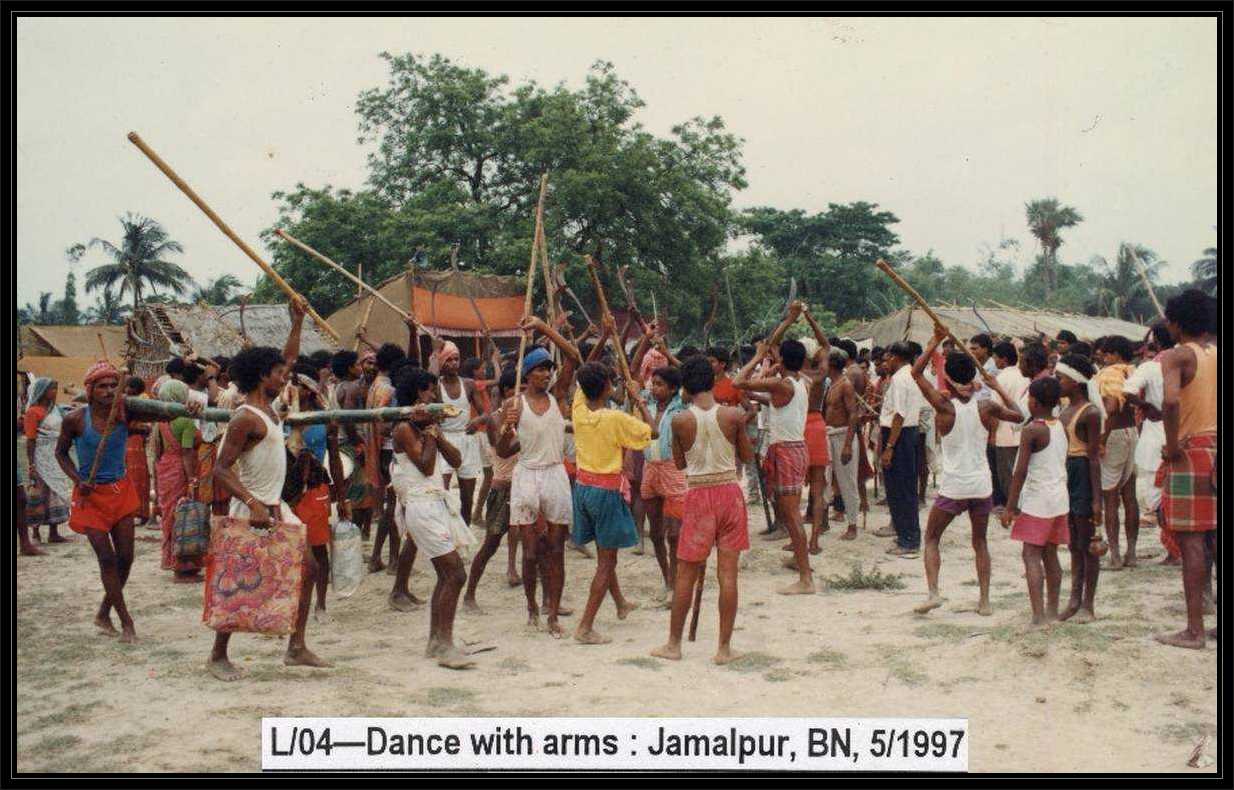

I used Ghose's short report of the late 1950s, published in 1959, as a guide as it helped me compare Jamalpur with what I saw myself up to 2001, which helped understand the slow but sure processes of appropriation and assimilation of an autochthonous cult into the mainstream religion. Ghosh had narrated how belligerence was a distinct feature of this festival in Jamalpur as mobs moved around quite openlyin the mela with weapons of all types. When I first visited thisannual fair in 1976 this aggression was still very evident during the village and continued unabated for the next 25 years. I have seen other festivals of autochthonous religion like Manasa and Chandi that have been 'Hinduised' more effectively and we may recall the "great trio" of the medieval folk deities on whom numerous balladic poems, the Mangal Kavyas, were written in Bengal between the 15th and 17th centuries. In this trio, it is only Dharma where the strongest elements of the earlier religious beliefs and practices still prevail. As I have explained in my The Construction of the Hindu Identity in Medieval Western Bengal: The Role of Popular Cults (2005), the Mangal Kavyas were an integral part of the response of rural Brahman and upper caste poets to integrate hitherto-untouchable forms of folk worship so as to win back their lost mass level support 4. The photos that I place as pics 8, 9 and 10 will display that time has hardly "sobered" the display and dances with arms. The first photo is from what Ghose, Konar and I saw in the second half of the 20th century and the next to show that this tradition continues, almost unabated, in 2014. These "martial gestures" are present, albeit in a more muted manner, in several sites of Dharma worship and often take the shape of fights (both mock and real) with lathis and other sticks. Jamalpur, however, is in a class of its own and Brahmanism can, at best, frown upon these rituals but even the police have not been able to stop them.

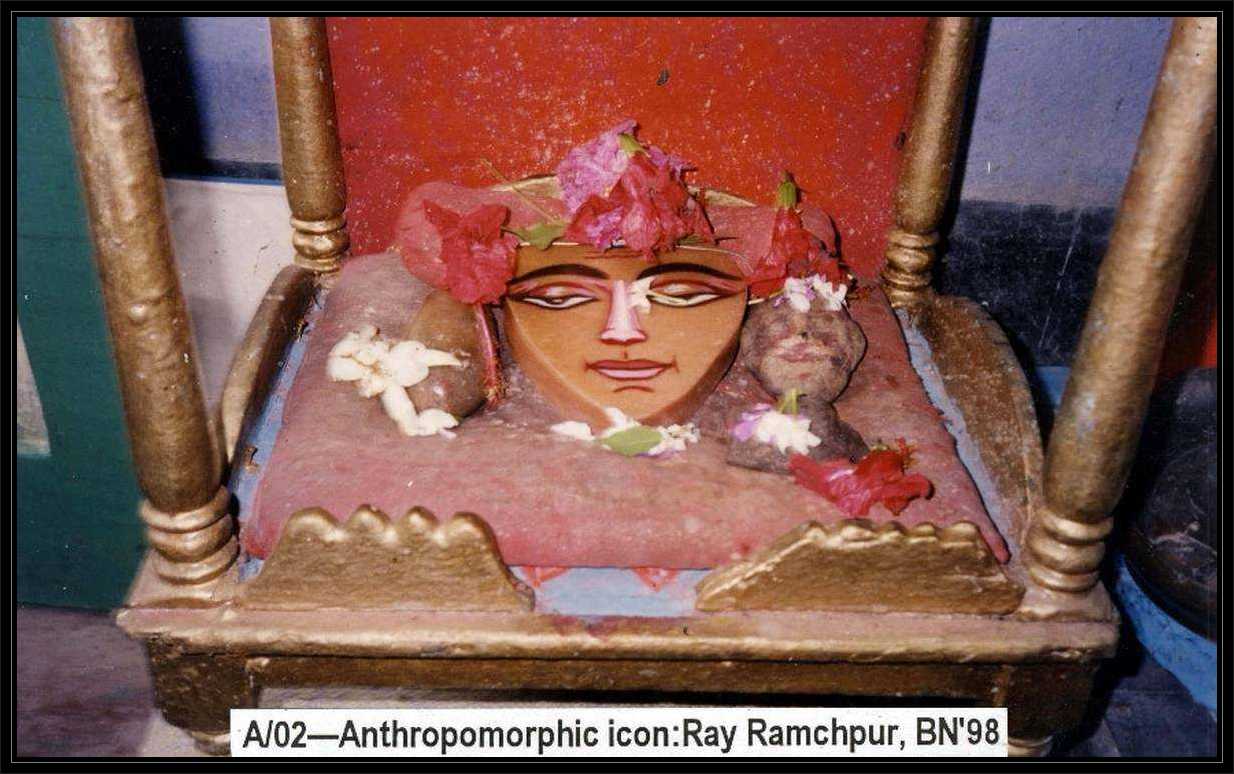

The autochthonous autonomy of Dharma worship comes out strongly in another matter, ie, its persistence of aniconic worship. While mainstream Hinduism provides for both the non-iconic stones like linga to represent Shiva or the shalagram shilas to be worshipped as Vishnu , while Shakti is often depicted as just stones, there is no doubt that the masses are more comfortable with the anthropomorphic or human image. Thus, there is a definite route that most the priesthood takes to bring pre-Hindu cults to join the mainstream religion and one of the critical steps to give the aniconic, shapeless stone an anthropomorphic shape. This could begin by drawing eyes on it (an example of such a Dharmaraj is placed at pic 11 ) or covering up the stone with human clothes, but here again, Dharma stands out in its autonomy.

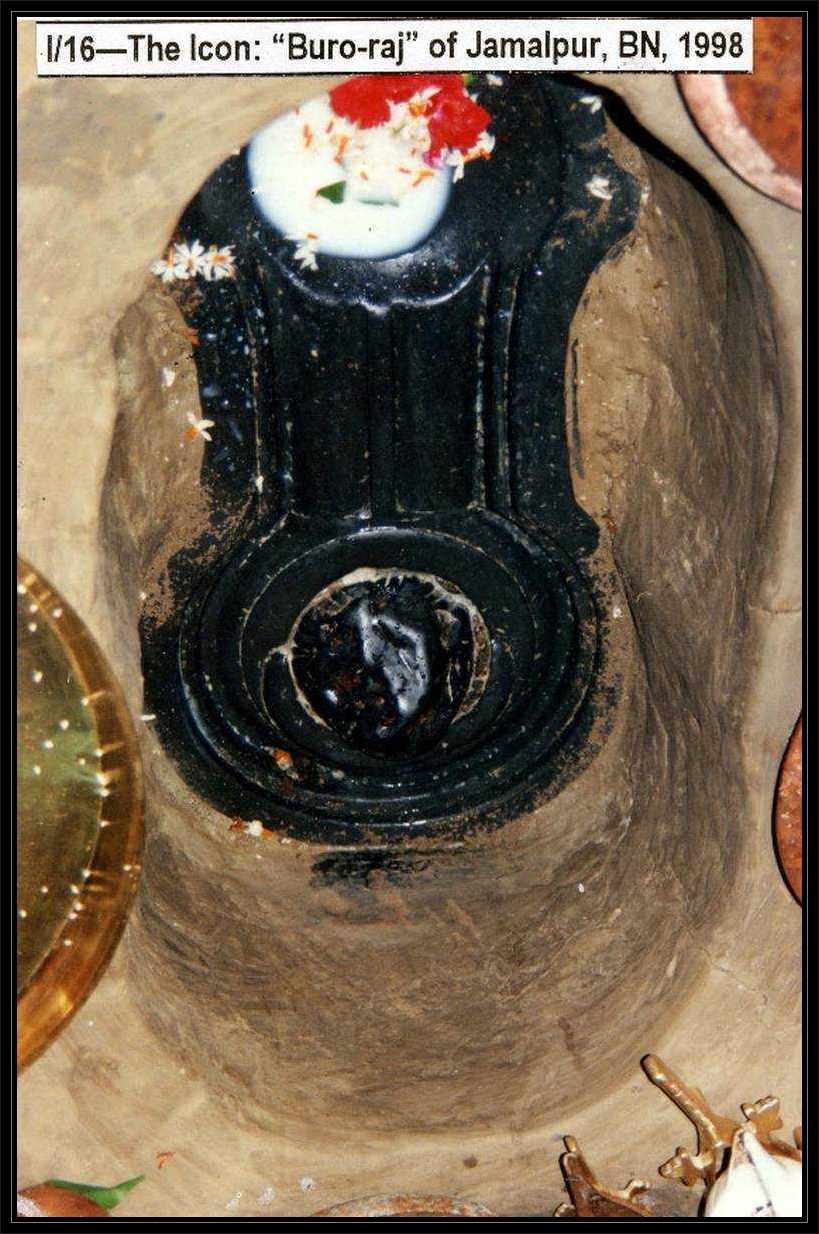

As the literate class has not been able to identify it definitely with either Shiva or Vishnu (it is either/or in most sites) and both or either mantras are used, the worshippers remain confused or away from it all. As a result, of all the old forms of cultic worship in Bengal, it is Dharma that is still worshipped in an iconic shape in all the sites we visited, just as one or more stones. In Jamalpur, he appears placed on a strange stone platform that looks like the Gauri-patta of Shiva, but it is not according to the classical shape, as pic 12 will explain. There are various stories as to which part of this image represents who, Dharma and Shiva. According to some versions, the rough stone stands for Shiva and the end, the empty circle is for Dharma, while according to other legends it is the other way round.

There is no doubt that the original worship was that of Dharma and the first official record I could locate was the Appendix to The Bengal Sanitary Rules of 1893 that clearly mentioned the site at Jamalpur as 'Dharma-Raj', which is the most common appellation of this deity. This also revealed that the gathering was rather big even in the 1890s as the administrative machinery had to make special arrangements for mass scale public latrines and water supply. Very interesting is the fact that the temple was recorded in the name of Nani Gopal Banerjee, who is definitely an ancestor of the present clan of priests. The noted scholar, who was the President of the Bangiya Sahitya Parishat and General Secretary of the Asiatic Society, Haraprasad Sastri, visited the site in 1893 and 1898 and insisted that the Dharma cult was a "vestige of the Buddhist period of Bengal" but this could hardly be substituted 5. He reported that there was just one rock, possibly a small meteorite, that was worshipped at thatched hut as Dharma Thakur. The fact that there was no mention of Shiva in 1898 reveals that the priests must have worshiped the single aniconic stone as Dharma only. But it is also clear that the Brahman priests had managed to introduce the standard legend of a how a "divine cow" had suddenly started pouring its milk on the ground at a specific spot and how this led to the revelation of Shiva's linga, in the form of a crude stone dug up from the soil. This facilitated the introduction of Shiva into the domain. Yet, we find from the next official record of 1921, the List of Fairs and Festivals publication of Mr C.A.Bentley, the Director of Public Health, that it is still called by the original name, 'Dharma-raj'.

It is only in Ashoke Mitra's Fairs and Festivals of West Bengal (1953) that was published after the 1951 Census operations, that the name 'Buro-raj' first appears. This name appeared not only at Jamalpur, but also in two other Dharma sites at Joshu-Bhagra and Icchudanga in Manteswar thana, so close to this place. Since the purohits were the first to be consulted by the authorities, there is no doubt that the Banerjee family of Jamalpur had finally got their way by giving Shiva an equal status, through use of legend; their socio-religious clout and official indulgence. This is a perfect example of 'appropriation' as a phenomenon that is different from 'assimilation' and 'accommodation'. Once ensconced, Shaivism would make its presence felt and would draw larger crowds of devotees throughout the year, as identification was easier and the legends of the might of Dharmaraj could always be leveraged. Shiva lingas are up for sale as the photo at pic 13 will explain and the increasing obliteration of Dharma's originality by the pan-Indian deity, Shiva, is no more in doubt.

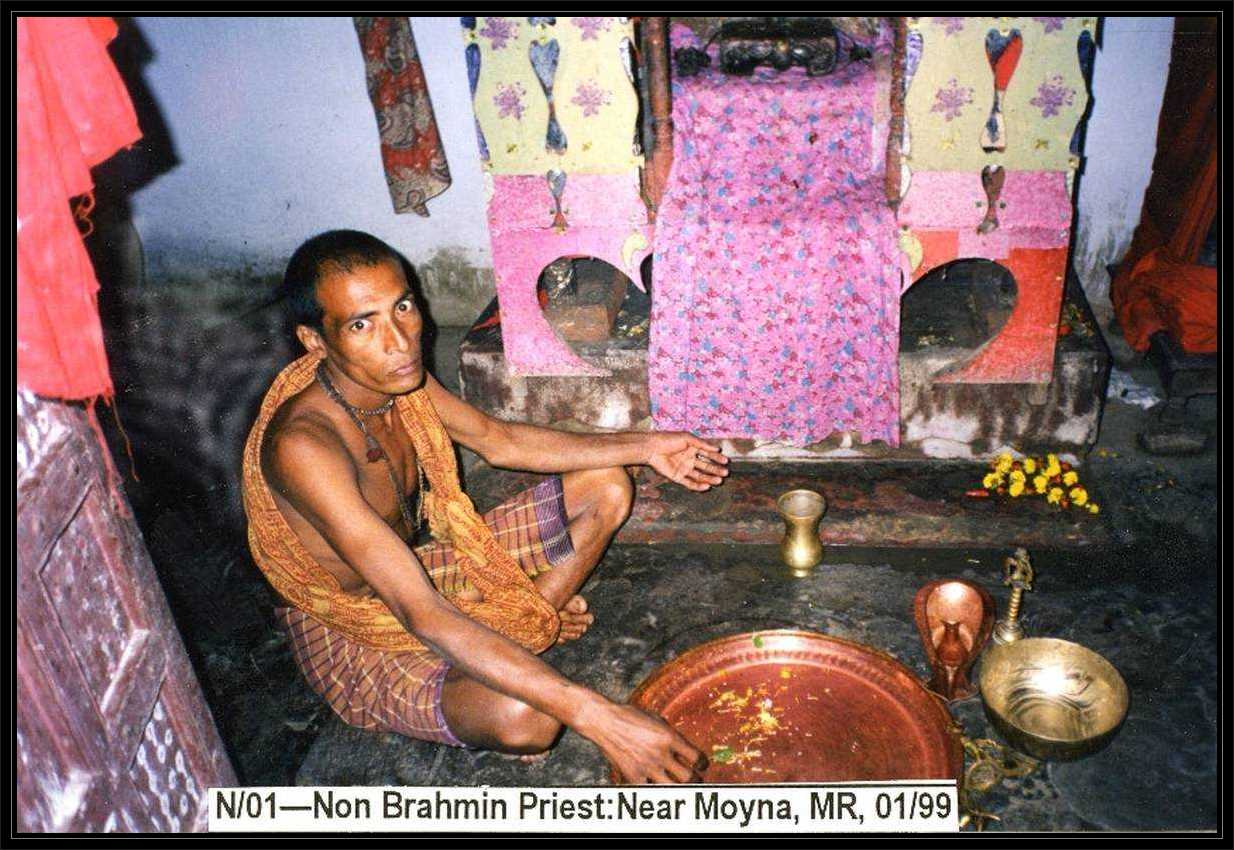

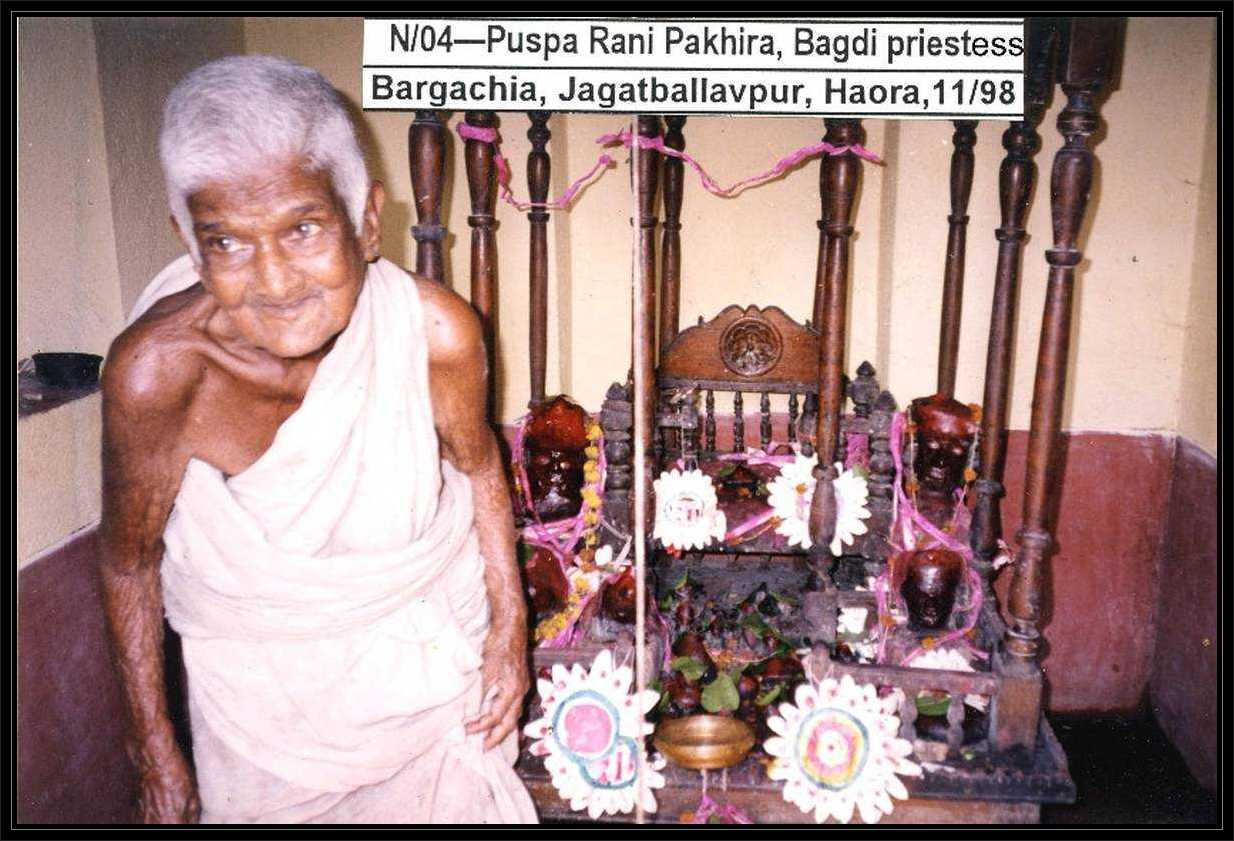

There are numerous more examples but we may delve for a moment on the original worshippers of the deity at Jamalpur. It is quite usually the rule at the sites of worship of folk deities that the original non-Brahman custodians of folk deities, usually from the so called lowest strata, also double up as priests for occasional festivals. I have placed two such examples of a non Brahman priest and even a priestess as pics 14 and 15 . The latter is interesting as Brahmanism do not permit women priests, but autochthonous religions were more liberal. The usual modus operandi for a Brahman purohit family to take over the worship at this site is to introduce daily worship according to prescribed rituals and then draw their sustenance from the donations of devotees. But the new Brahman priests sually take care to accord a specific task to the unseated former subaltern 'priests', like the Bagdis of Jamalpur, to keep them content. Since their earlier involvement was normally only during the annual festival, the strategy is ensure that they earn something during the festival, by escorting pilgrims, or helping in slaughtering animals (mentioned before) or even in repairing the thatched roof periodically, at community expense. There are many more issues but the size of this piece does not permit more discussion.

While ending this article that focuses on the appropriation and absorption of a pre-Hindu cult, one finds that the process is slow but fascinating because there is no proselytisation that is involved, nor any fixed date of conversion to a new form. The past is retained but a new narrative is slowly but surely superimposed, almost consensually as it meets with no resistance. Religion is, after all, a dynamic process 6where even in the case of the 'revealed religions', the core or the superstructure may remain reasonably constant but the internal pulls, pressures, churning and twists within the religion continue for ever. In many religions, there is hardly any fixed position that is absolutely unchangeable and the process that I have narrated reveals the internal dynamics of the Hindu world at the grassroots level 7, to the extent it could be understood by a keen observer.

Notes

1 Bhattacharyya 1939/1998: 64ff; Dasgupta 1976: 259 ff

2 Mitra, 1953; Konar 2003,

3 Ghose 1959 is an excellent narrative.

4 See also Momtazur Rahman Tarafdar, 1994: ‘The Dharma Cult and Muslim Political Powers ’,

5 Sastri 1894, et al and Sen 1945.

6 Chakrabarti 1992; Nicholas 2003.

7 Bose (1941) explains the Hindu Mode of Tribal Absorption.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Bhattacharyya, Asutosh. 1939: Banglar Mangal Kavyer Itihas . 1998: 8th revised edition; Kolkata: A. Mukerji & Co.

- Bose, Nirmal Kumar. 1941: ‘ The Hindu Mode of Tribal Absorption’ . Science and Culture, Vol. VII, No. 4, Oct. 1941.

- Chakrabarti, Kunal. 1992: ‘ Anthropological Models of Cultural Interaction and the Study of Religious Process’. Studies in History, Vol. 8, No. 1, (N.S), pp. 123-149.

- Ghose, Benoy.1959: Paschimbanger Sanskriti . Kolkata: Pustak Prakashan.

- Konar, Gopikanta. 2003: Barddhaman Jelar Puja Parban O Utsab . Barddhaman: Indu Publications.

- Mitra, Ashok, 1953. The Fairs and Festivals of West Bengal, Calcutta, Census Publication

- Nicholas, Ralph. 2003: The Fruits of Worship : Practical Religion in Bengal. New Delhi: Chronicle Books.

- Sen, Sukumar. 1945: ‘ Is the Cult of Dharma a Living Relic of Buddhism in Bengal’ , in D.R. Bhandarkar(ed.):B.C.Law Volume I, Kolkata: Indian Research Institute.

- Shastri, Haraprasad. 1894: ‘ Discovery of the Remnants of Buddhism in Bengal’, in the Proceedings of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Kolkata, December.

Srinivas, M.N. 1952: Religion and Society Among the Coorgs of South India . Oxford: Clarendon Press. - –– 1989: The Cohesive Role of Sanskritization and Other Essays. New Delhi: Oxford University Press

- Tarafdar, Momtazur Rahman. 1994: ‘ The Dharma Cult and Muslim Political Powers ’, in The Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Vol.39, No. 2, Dhaka, Dec.