During the UPA years, 2004 to 2014, Narendra Modi, CM of Gujarat, led the brigade of States on each and every issue that he felt militated against the federal structure of the Constitution. Thus, when he was elected prime minister of India in 2014, we had naturally expected him to strengthen the rights of states and were certain that he would take away several controversially acquired powers of the Centre. Within a month or so, it became abundantly (and shockingly) clear that the new PM had no plan to decentralise the Centre’s powers. Officers were instructed not only to retain those powers that already favoured the government of India — whether fairly or unfairly was not the issue — and seek frequent explanations from ‘errant’ and ‘difficult’ States.

I quit this Central dispensation within two years by resigning as national head of the public broadcaster, several months before my term was over. This was for a host of reasons, including the PM’s obviously autocratic distortion of our democratic and federal polity. Consultation with States became an empty ritual and the chief forum where large teams from the Central and the State governments had met for over six decades and debated so exhaustively on developmental schemes, the Planning Commission, was disbanded overnight. It was replaced by the Niti Aayog — which was packed with acolytes whose loyalty to the PM mattered more than their efficiency or public standing. Briefs on what to do next swamped in from corporate houses close to the regime, more so via the Niti Aayog. Government was soon taken over by highly-paid consultants, corporate lobbyists, advertising agencies and dubious intellectuals on easy rent. Among their briefs was was to repackage every existing welfare scheme; play scrabble with alphabets, acronyms and combinations — and then come up with catchy names, like ad-agency tag lines. And almost every one of these ‘new’ schemes had to carry the words ‘Prime Minister’ before their names — even when States were made to fund 40 to 50 percent of these schemes. This was followed by a host of parallel media-directed and bhakt-oriented campaigns that no Prime Minister (including Vajpayee) had ever done anything at all for India in the preceding 70 years. This ‘narrative’ was repeated every day by the PM, every minister, MP, government functionary and regime-admirer for the next decade.

To understand the psyche of over-centralisation, we must appreciate the insecurities of the perpetrators that are born out of inadequate education, limited exposure and constricted world-views. The resultant anti-democratic and anti-federal actions are only manifestations of this mental state. And, arrogance and belligerence are the hissing fumes that accompany their hegemonic assaults. This tribe brands federalism as a western graft in our Constitution imposed by outdated liberals who weakened the strong Bharatiya nation. They fail to fathom that it is the very arch on which Indic civilisation — with its vast regional, ethnic and cultural differences — rests. They are unable to understand that any attempt to centralise or homogenise would not only be dangerous, but absolutely antithetical to the very existence of a composite civilisation.

It is, nevertheless, true that our Constitution framed by liberals contains certain streaks of Central domination on a few select issues of federal relations. The terrible disturbances of post-Independence India, when the British left behind not only two hostile nations, but 14 major provinces and 565 princely states (many with separatist agendas) may have called for a hard ‘centralising’ spirit. Liberals expected that many of these provisions would be hollowed out with increasing maturity of the Indian state.

Among the chief irritants in federal relations between the Centre and opposition-ruled States is the institution of the Governor. Article 153 empowers only the Centre to appoint Governors with no mandate to consult the State. While he functions normally on the aid and advise of the Council of Ministers of the State, Article 163 says he has his own powers of “independent action” — which have proven to be a camouflage for “Centre’s domination” through its hand-picked appointee. Article 200 empowers him to withhold assent to a State’s Bill passed by the Legislative Assembly or to reserve it for the consideration of the President — read, ‘Centre’. Several Governors have been withholding Bills on numerous pretexts, just to assert the Centre’s powers, even after they have been admonished by the Supreme Court. The Governor of West Bengal has blocked the appointment of regular Vice Chancellors to universities all over the State for well over a year and the orders of the apex court to resolve this deadlock are moving at a snail’s pace. He and his predecessors have converted Raj Bhavan into a cosy office for the prime opposition party, to launch broadsides against the legitimately elected government — perhaps to repay the party for appointing him. A simple issue like changing the name of West Bengal to Bangla has been held up indefinitely by the Centre.

Withholding Central funding to States on different pretexts is a crude instrument used by this Central regime (and some past ones as well) to hurt recalcitrant ones. While the devolution of the State’s due share of taxes cannot be stopped— it can only be delayed — what is less visible is the Centre’s increasing tendency to augment its own share of revenue by adding ‘cesses’ on tax or ‘additional duties’. These are non-divisible and are appropriated by the Centre alone. It is then used to reward their “own States” or those governments run by parties that support the BJP and opposition-run States are usually deprived of these funds.

With much larger wealth at its disposal, the Centre has more than enough to fund beyond its own critical sectors — central police, defence, external affairs, infrastructure, national highways, railways, aviation, ports, water transport, postal services, communications and so on. Instead of passing on untied funds to States, it has developed a gargantuan network of Central Sector and Centrally Sponsored Schemes to reach out to the last person. Central Sector Schemes, like the National Rural Health Mission, are totally funded by the Centre but often come with strings attached. For instance, funding to West Bengal and some States has been withheld because it refuses to colour the health centres saffron and call them Aarogya Mandirs. Even the Health Grant of ₹870 crores allocated to West Bengal by the Fifteenth Finance Commission is yet to be released to the State as the Centre is arm-twisting, with several uncalled for conditionalities.

While Finance Minister Sitharaman never tires in announcing her Special Assistance to States for Capital Investment, which offers a lucrative 50-year interest-free loan for capital investment, it is subject to a whole series of requirements, called the ‘branding guidelines’. Central sanction of funds ₹4138 crores for 2024-25 has been kept on hold, while another five thousand crores for the previous two years show no signs of release. Not only this, but even funds for Food Subsidy of ₹ 9,290 crores under the PM Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana have been held up from 2021-22 onwards, on a very trivial ground that the scheme’s logo had not been inserted in the receipts being provided to beneficiaries.

The Central Government has also entered areas meant for welfare of farmers, animal husbandry and fishery — with Central Sector schemes. The Centre’s relentless march in reaching the voter directly is also quite evident in other programmes as well, like the Mudra Yojana and Credit Guarantee Funds for SMEs, PM Employment Generation Programme (PMEGP) for unemployed youth and Ujjwala Gas Cylinders for the poor. These areas are better served by the States, as the Centre does not have an army of grassroots field workers, which the States have, and pay for. During Narendra Modi’s regime, facts and propriety do not matter as his last-mile schemes to reach citizens and voters for his own branding and publicity campaign.

The patently unfair allocation of Central funds for building sports infrastructure comes out clearly when we see Gujarat’s share is ₹609 crore and Haryana’s at ₹89 cores. Of the 6 medals won by India in the last Olympics, 5 were from Haryana and none (ever) from Gujarat that sent only one player to Paris this time, against 24 from Haryana.

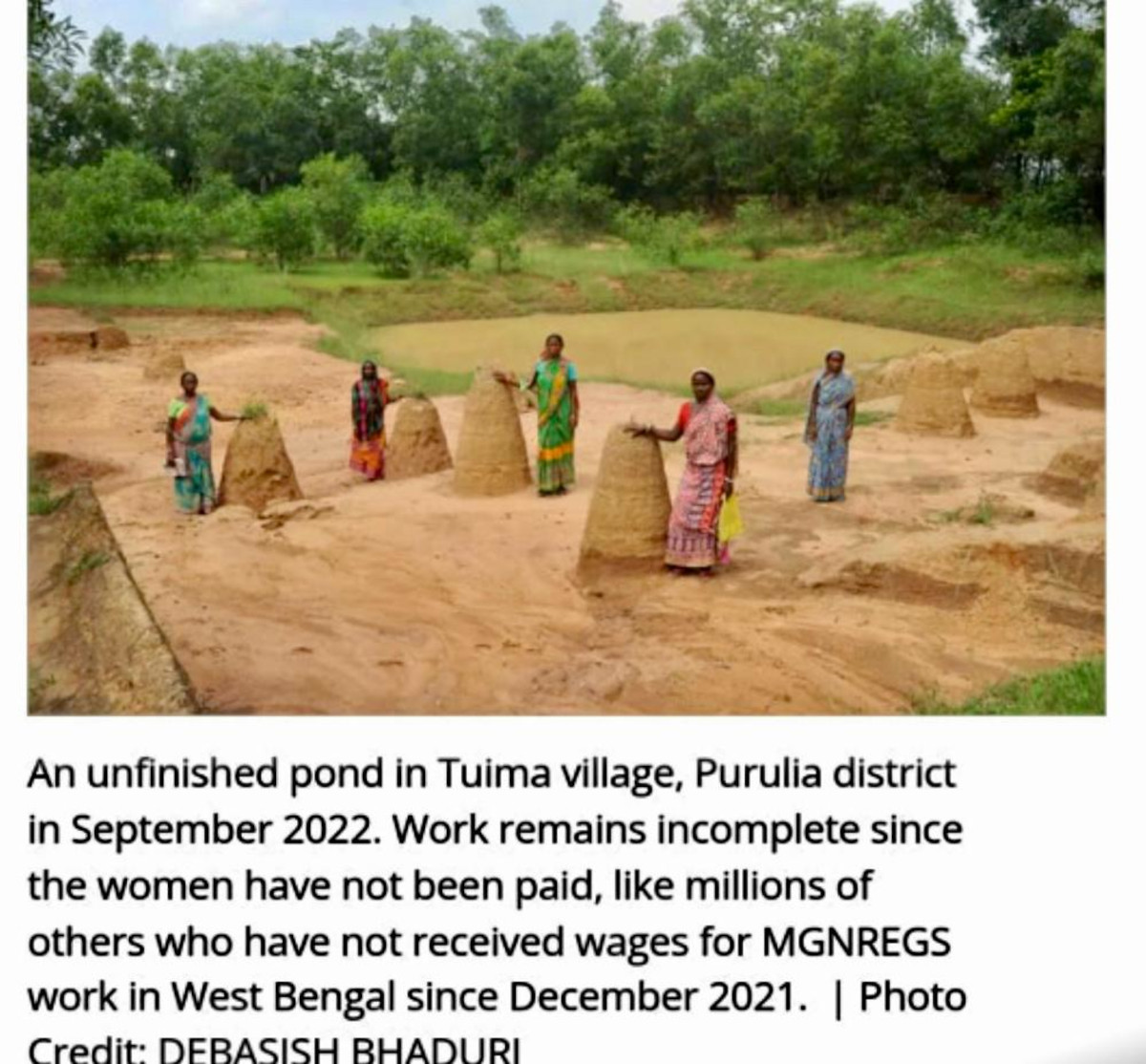

Then come Centrally Sponsored Schemes, that are designed to compel States with meagre resources to come up with substantial funding to avail of their benefits. Most of them carry the words “Prime Minister” in their prefix, like the PM Awas Yojna and PM Gram Sadak Yojana, for PM to appear as the sole saviour — conveniently omitting to mention that States also bear substantial contribution. The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Programme (MNREGA) emerged as the new battleground of federal relations. West Bengal was charged with irregularities in this vastly-decentralised programme, though the same defects were also found in 8 other States.

But Bengal was singled out for stopping all funds under Section 27 of MGNREG Act for non-compliance. The action-taken reports submitted by the State were rejected by the Centre, and till date, ₹ 6966 crores are yet to be released to the State. The State has put in place every measure of transparency required, including social auditing, appointment of ombudspersons, Aadhaar Based Payment System, public grievance redressal mechanisms and digital interventions. Even so, funds are choked as a purely political move — and voters have seen through it.

The PM Awas Yojana is another bristling point and the Centre has withheld its share to the tune of ₹ 8,140 crore since 2022-23 — citing insignificant reasons such as minor administrative corrections, variations in the execution of the schemes. Scores of Central teams were sent to the State and thereafter, the State submitted Action Taken Reports on every comment, along with necessary utilisation certificates and audit reports. Even then, the Centre is dragging its feet in releasing funds due to the State. Similarly, release of funds under Samagra Shiksha has been completely stopped since the end of 2023-24, as West Bengal did not sign the Centre’s one-sided MoU, which insists that the new schools be named PM-SHRI. A whopping amount of almost ₹20,000 crore stands as “receivable.”

Federal relations do not end with these tales of deprivation. There are no major Central projects or PSUs coming up to boost industry and jobs. The stoppage of Central anti-poverty schemes in West Bengal has increased the misery of the rural work force and a large section is compelled to find work as migrant labourers. Bank credit is always higher in those States where the political bosses are the same as the Centre’s. West Bengal has been off the danger-radar of bank branch managers for half a century now.

Big investments call for major involvement of the Centre — that still clears Foreign Direct Investment proposals; give nods to large loans by consortium of lenders and sanctions colossal amounts of subsidies as Production Linked Incentives. One needs to look at these benefits showered in Gujarat for obvious reasons and West Bengal is just out of these smart games. Even Startups that are flush with venture and other capital are all concentrated in Delhi, Mumbai and Bengaluru — where plutocracy and politics honeymoon.

The dangers of taking federal autonomy too seriously are laid out bare where West Bengal is concerned. Other upright States that differ with Narendra Modi are also paying their own costs. We have purposely avoided discussing the hegemonic use of Central Forces in states and the vindictive assaults by Central agencies. Just a few days ago, the Union minister for Home informed Parliament that the Enforcement Directorate had launched 132 money laundering cases against political persons since 2019 and that in five years, it could succeed in just one conviction.

Federal relations in quasi-authoritarian India are, thus, much too complex to be understood only in terms of the constitution, the law, politics, economics or finance. It is a vast human tragedy as well and history will be much unkinder to the despot than we are.